I admired the illustrations in this crumbling 3000 page turn-of-the-century dictionary, so I cut out

every single illustration to save. Small detailed illustrations have always excited me, from my

earliest memories of book reading. Despite being out of date, with much of its information incorrect or obsolete, I couldn’t bear the idea of all these detailed little illustrations in this dictionary being discarded. To me, they represent someone’s time and labor, and therefore have value, even if that value has no place in our current culture.

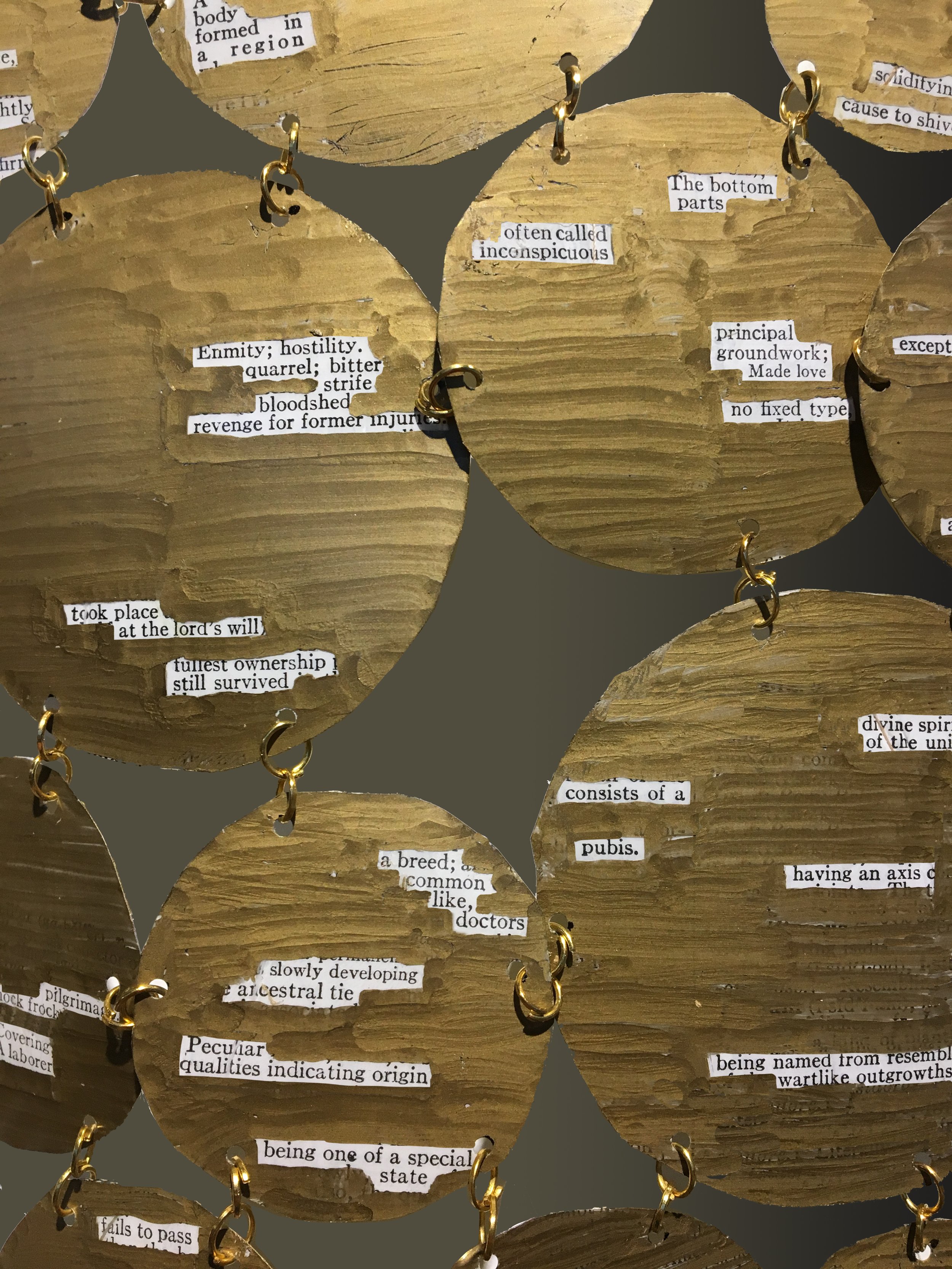

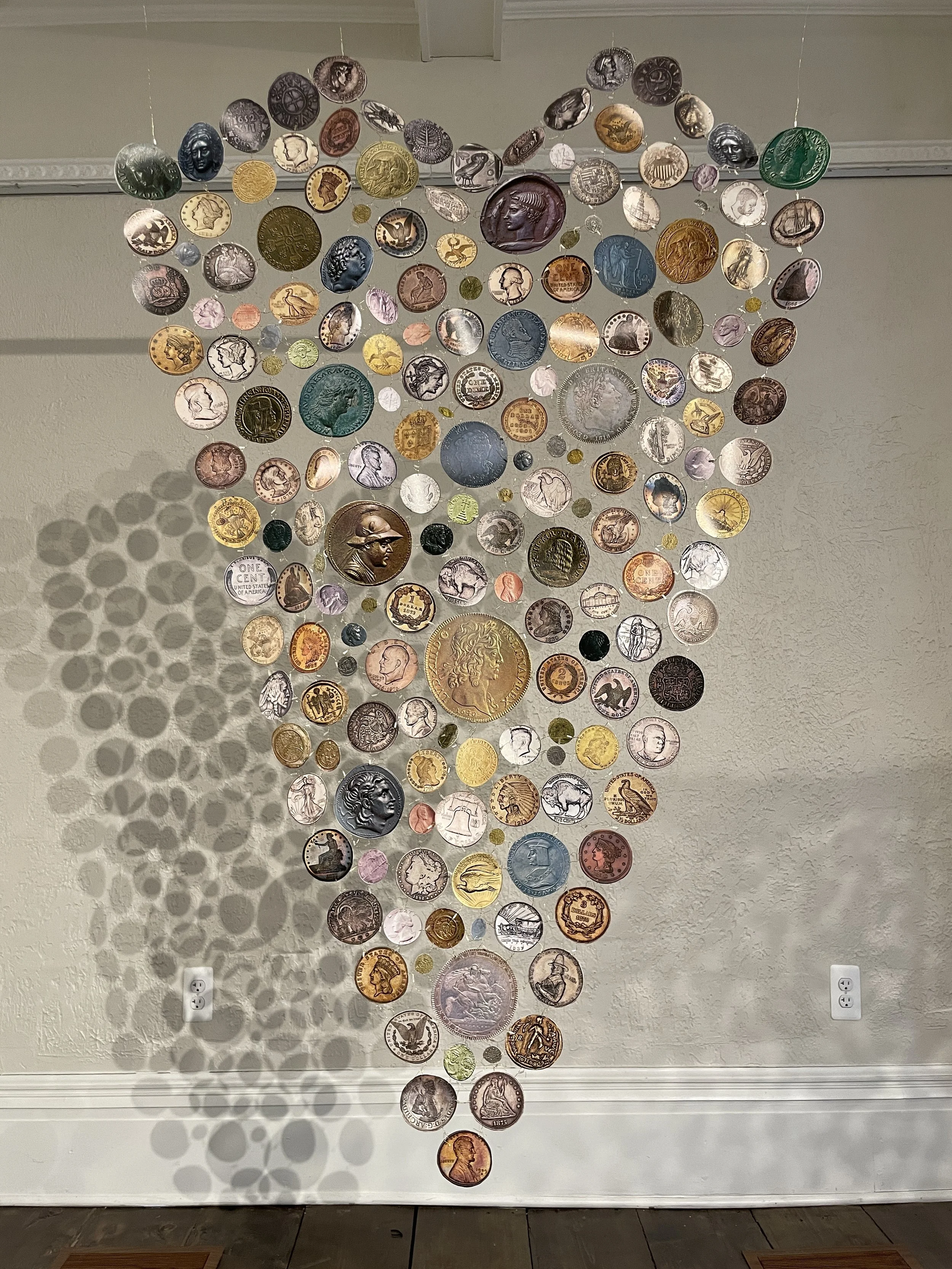

Cutting out circles came naturally as a way to frame and center each image. Circles with images suggested the idea of coins, and so I painted the space surrounding each image gold to illuminate that connection. On the back of each “coin” I tried to find vague but semi-sinister intent in the happenstance collection of words in proximity to each other, stringing together suggestive phrases that felt like a surreptitious undercurrent in a collection of knowledge that purports to represent truth and neutrality.

I have admired the artist El Anatsui for many years, and wanted to try using his technique of wired together bits of material to create draping textile-like forms. The circular forms and suggestion of wealth and armor reminded me of the feather capes that Hawaiian kings once wore, Ahu Ula. Creating a “protective” yet flimsy cloak suggesting past wealth in the midst of the pandemic seemed like an appropriate symbol for the omnipresent anxiety of 2020, a regal garment of questionable value.

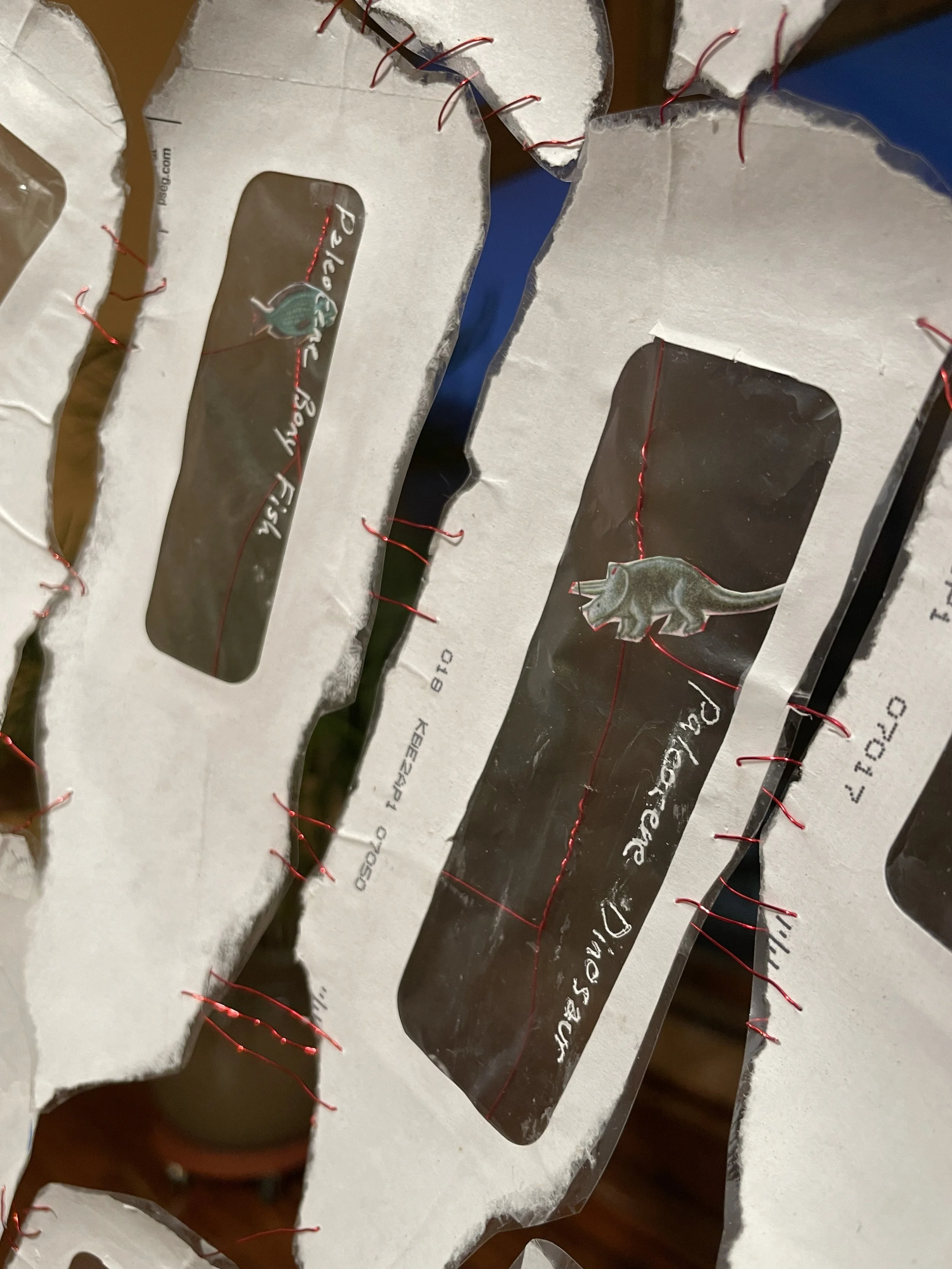

An entire chart illustrating the evolution of life on Earth, taken from a Golden Book Children’s Encyclopedia, is embedded in the windows of this fragile piece made of envelopes. It is stitched together with vein-like red wire that connects each species to another. We have received the many millions of years woven into this skin, every bit of which was required to make us who we are; it is our communal inheritance. We can preserve or discard it.

In the Greek myth of Icarus, hubris leads to catastrophic loss. This cause and effect formula underlies many of these works. In “Icarus”, hundreds of butterfly species, excerpted from a world encyclopedia of lepidoptera, have been collected like beautiful specimens and harnessed to each other in pursuit of an arrogant goal. The very act of traditional butterfly collecting negates their ability to fly; here, the delicate violence of stapling all these creatures' wings together denies the functionality of the result. Possession becomes Midas’ touch: what is extracted in excess from the natural world begets our downfall.

This piece is from my “Outer Wear” series, which consists of clothing-like sculptures that express a longing for protection from both the mistakes of the past and the revenge of the future. Each “garment” is composed of many small images, culled from collections of scientific printed reference material. These materials, static and fixed in time, feel nostalgic to me because of their tactile existence and assumed objectivity, when so much of what we take for granted has become virtual and/or tenuous.

“Parental Poncho” is composed of both of my parents’ CAT scans. Obviously non-functional as protection, it is made up of images that are the most intimate and most anonymous visual representations possible - I am looking at the inside of my parents’ brains, yet who they were is nowhere to be found. And while this garment can surround me with my parents, I am exposed nevertheless. When I think of all the ways my parents tried to keep me safe, I become aware of the ways they could not protect me as well, just as I cannot protect my children from much of the world.

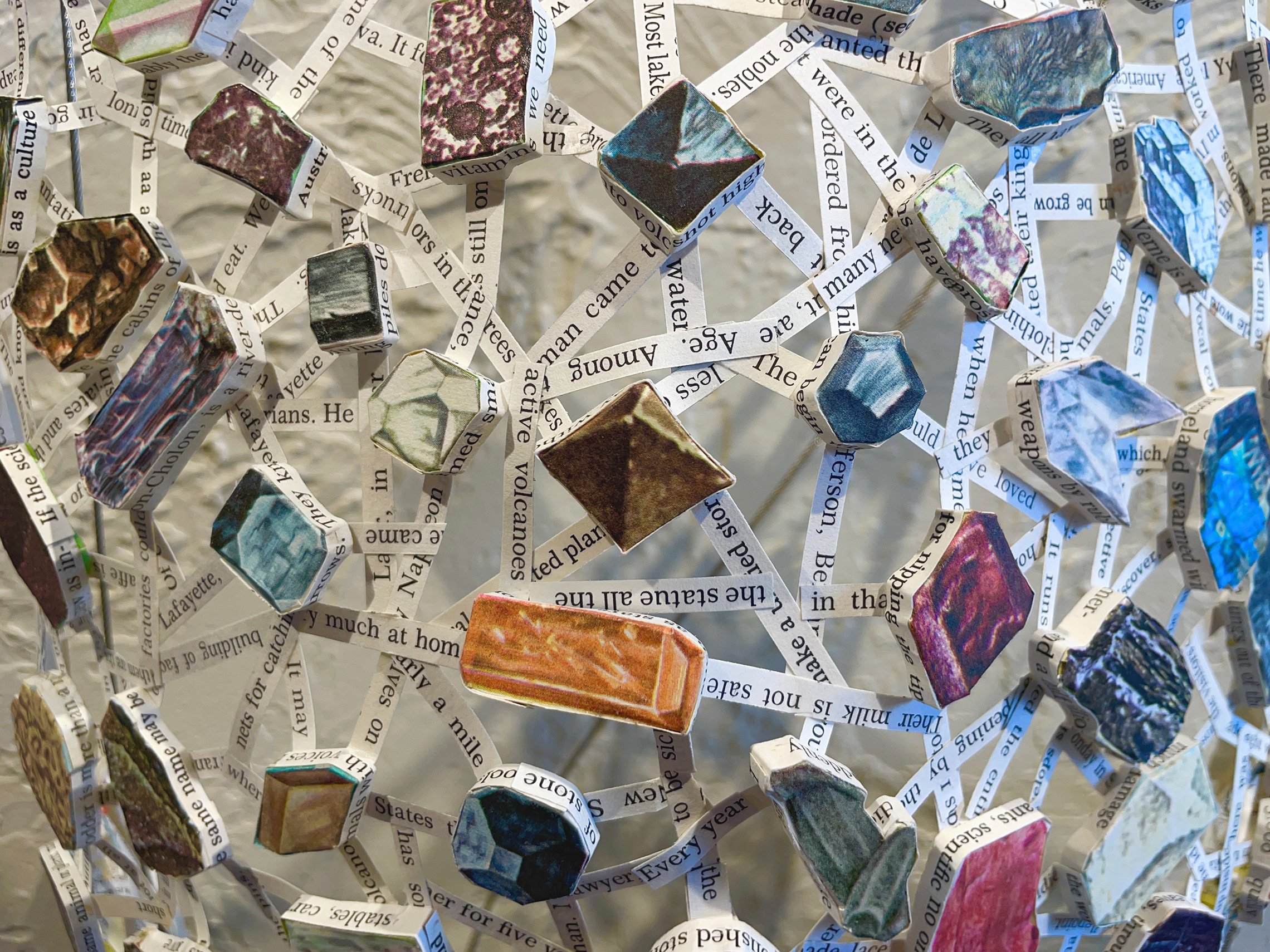

This cuirass is made up of, and covered with, images of ore from a 1960’s children’s book of minerals from around the world. I extracted the minerals from the book just as they might be extracted from the earth, thereby rendering the book useless, and heightened the “value” of each specimen by investing additional labor in by giving each one dimension. The idea that mineral wealth might protect us is undermined by the inherent fragility of this object; there is no such thing as protection from the human habit of extraction.

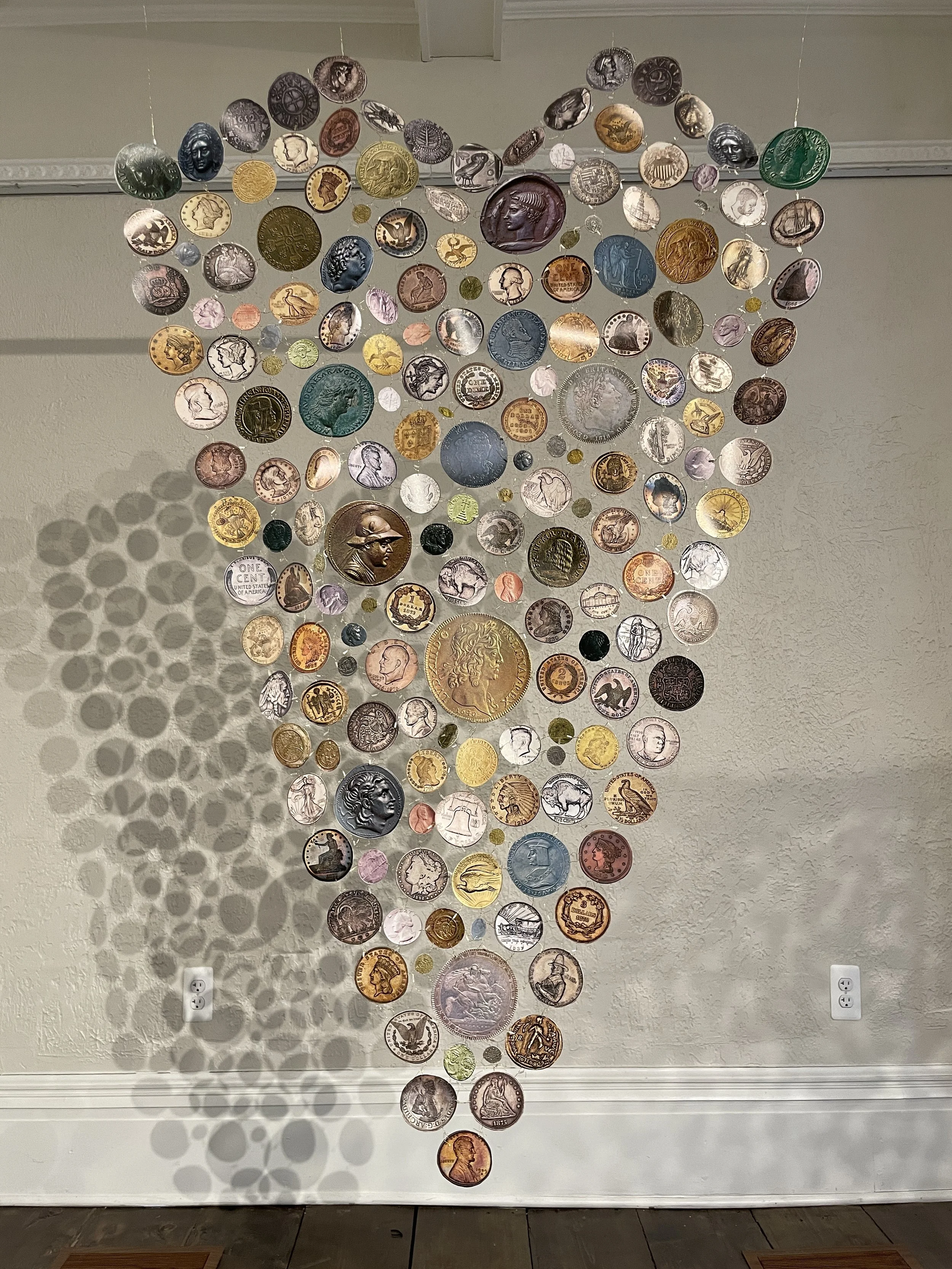

This vestment, made of historic coin images, features heads of state and symbols of power. Money can be a protective strategy, a way to fend off threats from the world at large. But it also can cloud introspection, conflating self worth with external value. Therefore the reverse side of this garment is mirrored, revealing a distorted reflection to the viewer as a parallel for the false identity of wealth.

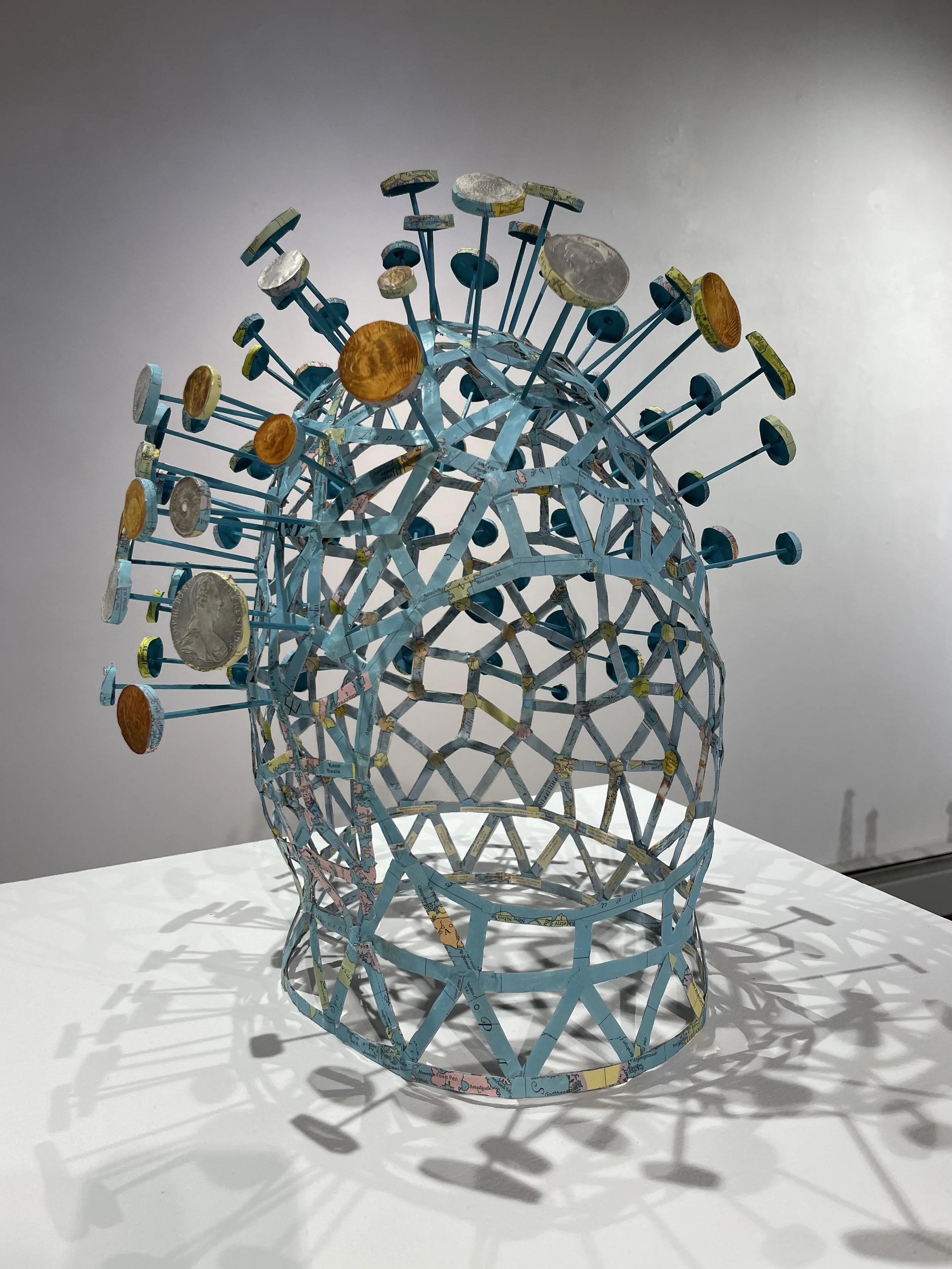

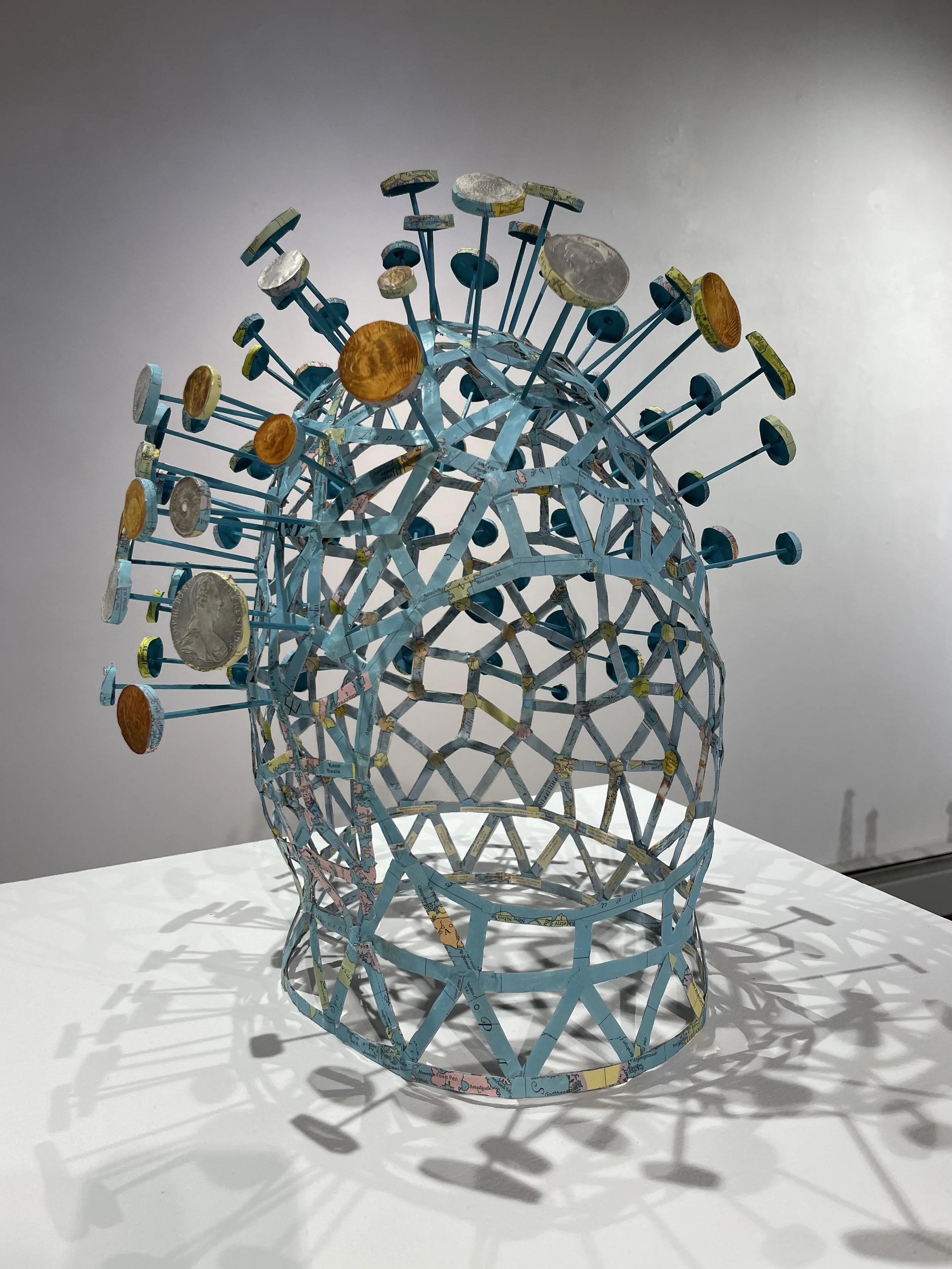

Caput means head, but sounds the same as kaput, meaning something is finished in a terminal sense. This helmet pretends that you can divide up, conquer, and possess the world and its resources; the wearer becomes the center of that world. The coins, mainly from colonizing countries, hover around the globe-like head piece to create a sort of protective barrier. The currency, made of repurposed maps, represents individual countries and the wealth they have accrued by claiming ownership. The coins reach out into space, the actual boundary for our species, the next place to colonize. While this piece was made before the Titan submersible event, it reinforces the false equation of money = protection.